Directionally correct predictions of higher education's demise

This week, I was reading Noahpinion’s (a.k.a. Noah Smith’s) most recent blog post - a review of “The End of the World is Just the Beginning” by Peter Zeihan, which predicts the collapse of global trade and the political fallout destined to change our ways of life.

I particularly loved this paragraph:

Which is not to say I think this book isn’t worth reading. In fact, it is worth reading, for two reasons. First of all, there’s a decent likelihood that many of Zeihan’s predictions are what businesspeople euphemistically call “directionally correct” — i.e., vastly exaggerated, but containing important seeds of truth. Second of all, the book functions extremely well as a disaster scenario — a vivid picture of what could happen if the human race allows globalization to collapse.

Let me explain why it struck a chord with me. This description, minus the part about the human race allowing global trade to collapse, applies to soooo many doomsayers in higher education for the last two decades.

Do you know how many books have been written predicting higher education’s swift demise? I don’t know exactly how many either; I just know that there have been a lot. Here’s a random list of just SOME of the higher education doomsayer and doomsayer reaction books that I actually own hard copies of (these were just the most immediately accessible):

- American Higher Education in Crisis? by Goldie Blumenstyk

- Beyond the University: Why Liberal Education Matters by Michael Roth

- Crisis in the Academy by Christopher Lucas

- Crisis on Campus: A Bold Plan for Reforming our Colleges and Universities by Mark Taylor

- College (Un)Bound: The Future of Higher Education and What it Means for Students by Jeffrey Selingo

- College: What It Was, Is, and Should Be by Andrew Delbanco

- Reinventing Higher Education: The Promise of Innovation edited by Ben Wildavsky, Andrew Kelly, and Kevin Carey

I am not drawing attention to my book ownership here to brag. I’m not in the business of collecting these volumes or anything. What I’m trying to illustrate is that you can’t swing a dead cat without hitting an author thinking deeply about the crisis of higher education and its incoming ruin. Whether they think higher education has been reduced to an expensive signaling device (Bryan Caplan), will be disrupted by online learning to a point of unrecognizability (Clayton Christensen), or will lose its place in our world due to political agendas (Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff or Will Bunch), we have no shortage of hot takes on the matter.

What we do have is a shortage of is predictions-come-true. The thing is, some of these books are getting old now, and the higher education market is still kickin’. So, what are we to think about this perpetual dark cloud hanging over our entire industry?

Correctness of Direction #

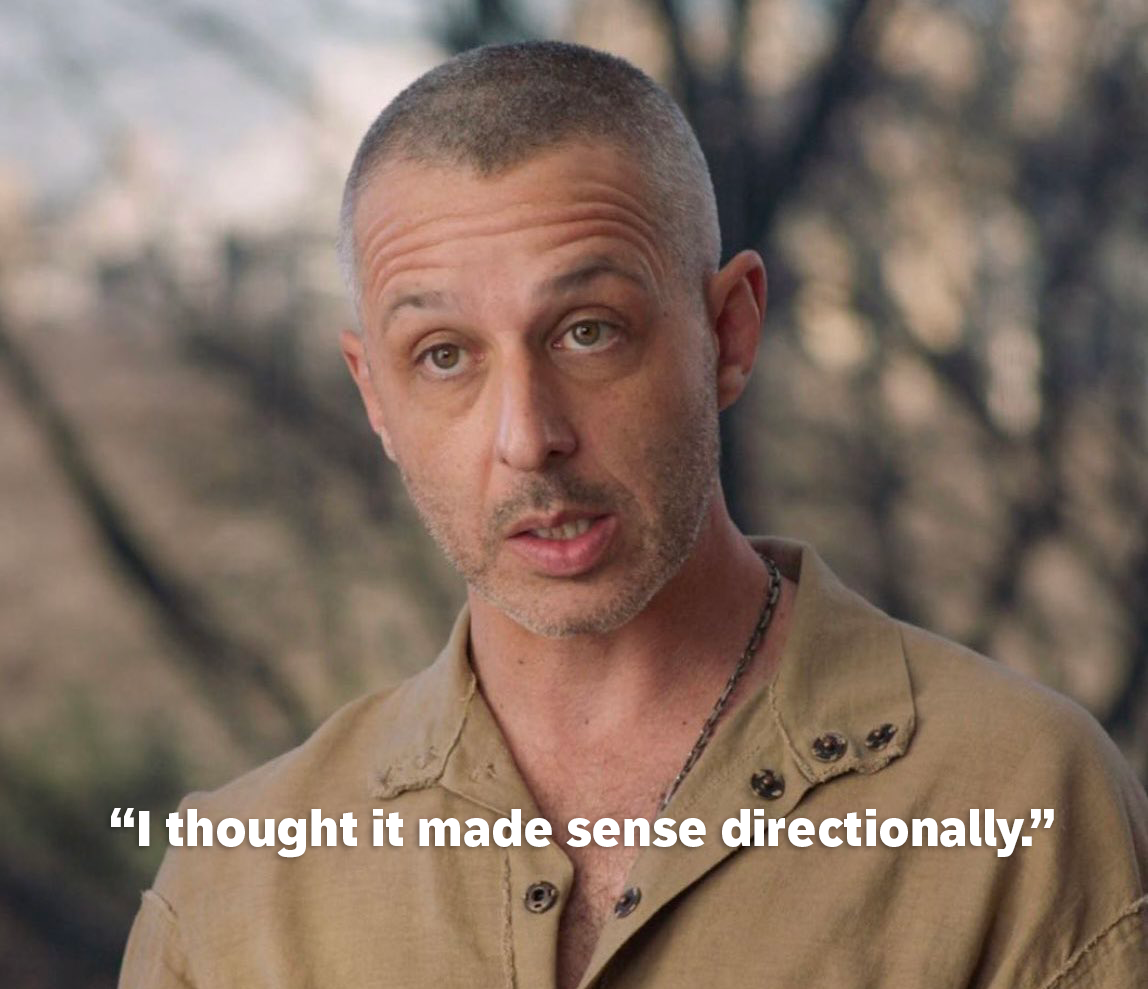

“Directionally correct” is some business jargon that either hasn’t punctured my attention bubble or I’ve somehow managed to dodge entirely (like playing the Little Drummer Boy challenge during December). Now that I know it, though, I can’t wait to shoehorn it into conversations.

“Your fantasy football draft plan seems directionally correct to me.”

“Your approach to planning our Norway trip is maybe directionally correct.”

“That was a directionally correct assumption about what I wanted for my birthday.”

The reason this buzzwordy phrase is so enticing is that it’s conceptual agreement plus an unexpected insult. It’s like saying, ‘Your intuitions are right, but your conclusions are still bat shit.’ It’s so delectably judgey!

And, if we take stock of all the predictions of higher education’s crumbling, we can see that it’s been a remarkably resilient industry. Yes, it’s slow to change. Yes, it’s suffering some consequences. But, it’s not evaporating before our eyes or being replaced by for-profit coding schools.

First, despite the rumors, a college degree provides upward social mobility. You do have to finish a credential to see the effects, but the effects are real and strong. According to the American Enterprise Institute and the Brookings Institute, children born in the lowest income quintile who do not earn a four-year degree are four times as likely to wind up in the bottom (47%) as those who earn a four-year degree (10%).

Second, higher education is associated with a number of positive outcomes, including lower smoking rates, more positive perceptions of personal health, higher levels of civic participation, and lower incarceration rates than individuals who have not graduated from college.

Third, the worldwide higher education market is expected to grow by 10.3% between 2022 and 2028. We all have good reason to pay attention to the domestic demographic changes and the impending enrollment cliff. But, we also have reason to believe that global demand will continue to grow with our global population. And, right now, institutions in the U.S. still enjoy a reputational advantage.

Seeds of truth #

So in what direction are these doomsayers correct? Higher education is riddled with problems. And, we need to be responsive to them.

I remember back in April 2020, a friend of mine who was doubting Covid-19’s ability to wreak havoc on our health and healthcare system asked me, “Kristin, if it’s so devastating, where are the bodies?” He was operating on that whole notion, “…and they give it to two friends, and they give it to two friends, and they give it to two friends” and KABOOM - everyone has it in two weeks or less. For him, the math simply didn’t add up.

Similarly, the refrain, “We’ve got to adapt!” has left us with the expectation that we need to be innovating all over the place to save ourselves from the fates of Idiocracy. But, innovations don’t have to be big and flashy to be successful. Subtle innovations and shifts are happening all around us. Not all of them are publicized yet because A) higher education researchers aren’t done researching them, and B) they might be offering their institutions a competitive advantage right now that institutions will want to hold onto for as long as they can.

If we have many competing innovations all at the same time, we don’t know how to properly attribute our successes and failures. The rate of innovative change can only go so fast and so far at once.

Scenario planning #

The other part of Noahpinion’s paragraph that I liked was when he said Zeihan’s book “functions extremely well as a disaster scenario.” Like Galadriel showing Frodo and Sam her mirror, these higher education doomsayer books show only a potential future, and not a broad, sweeping one, but possibilities on the institutional level.

That means we could use them to gather symptoms, take stock of our environments, and respond before we meet our fate.

I say all of this to encourage both your skepticism and your professional adaptability. It’s important not to overreact to the-sky-is-falling messaging haunting higher education. It’s equally important to keep tabs on trends and be nimble enough to respond quickly and precisely when the time comes. If you see posts that pontificate that “higher education as we know it will be extinct in 20 years,” you can likely dismiss the broad claim. Again, our industry is resilient. It has faced challenges before, and it will continue to face challenges. We will need to adapt. But, that doesn’t mean that we’re blindly and inexcusably following the dodo into oblivion.

It does mean that we have to continually renew our responses to challenges, especially at the institutional level, in order to stay healthy and competitive.