The Relationship Between Psychological Safety and Professional Development

This month, Bravery Media has been talking a lot about Professional Development. We’ve launched a Professional Development Survey - if you haven’t taken it, I hope you do. We’ve released a few Appendix B episodes on the topic. And we’re currently in the process of planning our own conference and event attendance for the coming year.

One thing we haven’t talked about through hot takes, podcasts, presentations, or workshops, though, is psychological safety. Most of the time, we hear about psychological safety when we’re in conversations about workplace well-being and culture, diversity and inclusion, and employee resilience and retention. But, we rarely hear about psychological safety in conversations about professional development. And the fact of the matter is that psychological safety is an essential component of any effective professional development practice.

First, let’s understand what psychological safety is. Psychological Safety is a newer concept coined in 1999 by Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson. She explains that psychological safety is “a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking.” In other words, “it’s felt permission for candor.”

Within the last 25 years, psychological safety as a construct has taken the world of organizational psychology by storm. According to McKinsey, a staggering 89 percent of employees across various industries believed that psychological safety in the workplace is necessary for their effectiveness.

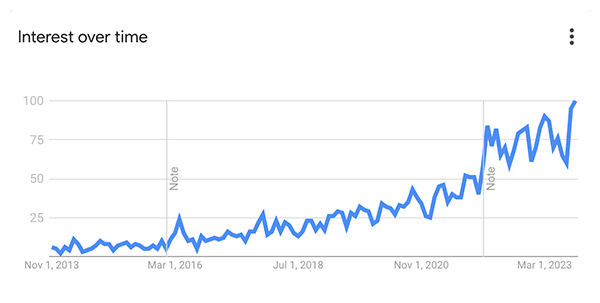

According to Google Trends, from 2013 to 2021 the term psychological safety had steadily grown in searches. Then in 2021, after many firms broached bringing staff back into offices, the term spiked. Having just faced a pandemic, heightened racism towards Asian Americans, and the murder of George Floyd, American workers were concerned about their mental health in the workplace. And, it is no surprise that the spike in interest coincides directly with a spike in searches and stories about the great resignation.

Based on these facts alone, you probably think about psychological safety when considering diversity and inclusion or workplace well-being. So, it might surprise you to know that Amy Edmondson has always investigated psychological safety through the lens of organizational learning. That’s right; I’m not tying together two disparate ideas here. Psychological safety’s birthplace is in understanding effective professional development.

Amy Edmondson began her career by studying how professionals and organizations learn from mistakes. Her research interests quickly evolved to studying the qualities of learning organizations. And that’s when she landed on psychological safety. In her study “Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams,” Edmondson demonstrates that psychological safety is associated with team learning behavior. Since then, she’s written books such as The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth and Teaming: How Organizations Learn, Innovate, and Compete in the Knowledge Economy.

There are some important aspects of the relationship between psychological safety and professional development I want to draw to your attention.

- A necessary part of learning is practicing. First, we have to figure out how to apply any new knowledge we have to a problem we’re looking to solve. Then, we have to test our solution to ensure it will work. Often, practice takes time because we’re naturally slower at the things we’ve never done before or are less familiar with. Time and safety to practice are essential for learning.

- A necessary part of learning is making mistakes. Mistakes teach us about the limitations of our knowledge and skills or the applications of certain processes. Mistakes take time to recover from and reset. Time and safety to make mistakes are also essential for learning.

- Time is part of psychological safety. If you have no slack in your processes and no downtime, you do not provide psychological safety.

- Even when individuals learn new skills, it often impacts the entire team. Practicing new skills or processes, seeing and responding to mistakes, and coordinating changes often require the cooperation of others.

- Professional development is often wasted. People will not take risks when mistakes are made to feel costly. People will not share ideas or alternatives when there is no safety to speak candidly. If a person cannot share ideas or alternatives, and that person is the only one on your team with new knowledge acquired from professional development, your professional development initiative has failed.

So much professional development is wasted because we don’t even allow the time for people to practice and make mistakes on an individual basis. Affording entire teams the time to collaborate in practice and risk making mistakes together is almost unimaginable.

I cannot say this more emphatically: It is not enough to send someone to a workshop or a conference. It is not enough to pay for a course. In fact, you will be wasting valuable dollars if you don’t also make psychological room for people to share what they’ve learned with their team, reflect on how to apply their new knowledge, collaborate with team members, and recover from the mistakes they are naturally going to make through experimentation. Your professional development investments will be wasted if your team members cannot share what they’ve learned and propose new alternatives, if they can’t interrogate or adapt solutions to your specific context, and if they can’t experiment without running a great personal risk to their work relationships, their reputations, or their careers.

I cannot give you a full list of action items to bolster psychological safety. That would take a much longer hot take. What I can do is share my top three methods for generating the psychological safety necessary to take full advantage of professional development. The first one should be pretty obvious now:

- We have to stop focusing on “doing more with less”/”doing a little bit of everything.” Instead, we need to free up some time to innovate and do a few things well. We need to be realistic about what we have the bandwidth for rather than looking for Jacks and Jills of all trades and all those special unicorns. And we need to give our team members the time and space to concentrate, practice, make mistakes, and recover.

- Stop seeing people as their titles. Look, Higher Ed is deeply entrenched in a hierarchical madness. But, if you want to immediately engender a feeling of psychological safety, treat everyone with the same respect with which you would treat the president of your institution. If the president of your institution could ask you about your reasons for a particular decision, you ought to be able to provide some kind of response to Sally from the Graduate School even if you think it’s none of her business. If the president could ask you to reconsider the workload you’ve assigned to Jeff, it’s reasonable to hear Jeff himself explain why it might be too much. If you feel a sense of urgency to get back to your Dean or your Associate Vice Provost, maybe you shouldn’t put off answering that question about committee assignments from your administrative associate. Treating people with the same level of dignity and respect will reduce their anxiety and support their sense of trust and candor.

- Focus on facilitation. I personally think facilitation skills are an unsung leadership superpower. Holding generative conversations, drawing out important insights, surfacing latent tensions, and crystalizing key decision points - not to mention running productive meetings - this is what makes all the other work possible. The better you and your team members are at facilitating, the better you can be at making progress, reducing stress, and connecting with one another - all ingredients for feeling psychologically safe.

I’m not writing about this because it’s a personal interest of mine. Bravery has a dog in this fight. Part of the work we do is education. Education is part of every transformation, and even when we’re only designing or building a new website, we’re still entering into a transformative process with our clients. We want to see that education and transformation have a long-lasting, positive impact on our clients.

Side Note: If you get the chance, please take our professional development survey, share your insights with us, and help us learn about what we can do to support you better in the future.